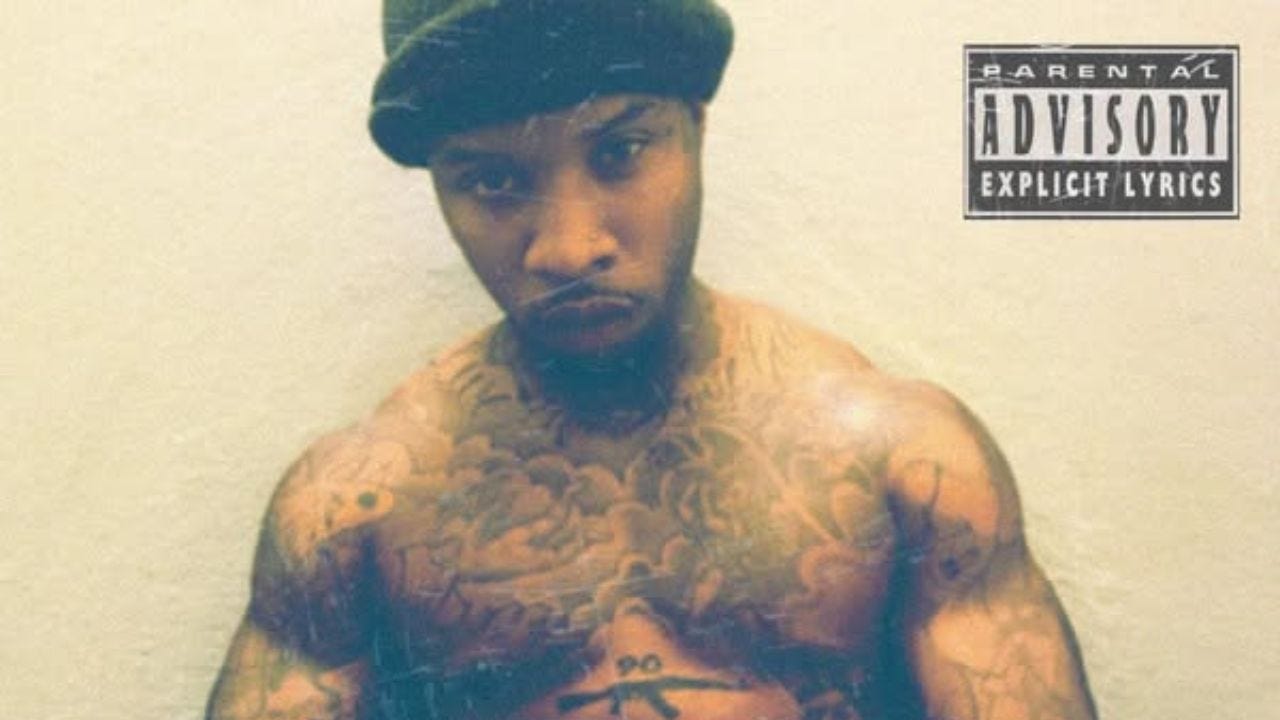

TORY LANEZ’S PETERSON: BARS FROM BEHIND BARS

The Science of Art and Redemption

In the ever-evolving world of hip-hop, controversy and creativity often walk hand in hand. Tory Lanez’s latest album, Peterson, is a testament to that paradox—a body of work recorded from within prison walls, challenging the limits of artistic expression under confinement. The Canadian rapper, currently serving a 10-year sentence for the 2020 shooting of Megan Thee Stallion, has turned his incarceration into an unlikely creative sanctuary. But does Peterson mark a bold reclamation of his artistry, or is it simply another self-mythologizing narrative in rap’s long history?

THE PRISON ALBUM: A FIRST OF ITS KIND?

Lanez has dubbed Peterson the "first ever in-real-time prison album," and while hip-hop has long been intertwined with the criminal justice system, very few artists have recorded and released a full studio album while incarcerated. Historically, artists like 2Pac and Lil Wayne dropped projects while in prison, but these were mostly pre-recorded tracks or unfinished materials polished by producers on the outside. Lanez, however, attempted something different—recording vocals behind bars and collaborating remotely with producers such as 2one2, Lex Luger, and Sebastian Lopez.

The result? A raw, gospel-infused record that leans into themes of self-reflection, faith, and survival. But it’s impossible to ignore the elephant in the room: the blurred line between artistic redemption and moral accountability.

HIP-HOP, INCARCERATION, AND NARRATIVE CONTROL

Prison narratives in hip-hop are nothing new. From Meek Mill’s Championships to Boosie Badazz’s Incarcerated, rap has always been a vehicle for artists to process and portray their experiences with the justice system. However, where most prison albums focus on systemic oppression and the struggle for freedom, Peterson takes a different route.

Critics like Rolling Stone’s Mosi Reeves have pointed out that Lanez frames himself as a misunderstood figure, draping the album in “self-centered liberation dreams and misogynoir sleaze.” Lines blurred between personal redemption and defiance, the album’s tone fluctuates between self-pity and self-empowerment. With guest appearances from his family, including his father, son, and brothers, Lanez attempts to reconstruct his public image as a man of faith and responsibility. But does it work?

SONIC LANDSCAPE: REDEMPTION OR REPETITION?

Musically, Peterson showcases Lanez’s versatility. Known for his ability to shapeshift between R&B, trap, and dancehall, he infuses gospel-tinged melodies with the usual bravado of a hip-hop artist trying to regain his throne. The production is clean but lacks the groundbreaking innovation of his earlier work. Instead, the album is built on familiar sonic textures that, while polished, fail to push new boundaries.

Guest features from underground and rising artists like Jaquain, King Midas, and DSTNY bring a collaborative feel, but the weight of the project rests on Lanez’s shoulders. Some tracks feel like an attempt to win back the audience, while others serve as direct statements on his incarceration.

FINAL THOUGHTS: WHAT DOES PETERSON MEAN FOR HIP-HOP?

Lanez’s Peterson is, if nothing else, a significant cultural moment. Whether viewed as a genuine artistic expression or a calculated move to control his narrative, it adds another chapter to hip-hop’s complex relationship with crime, punishment, and redemption. Unlike Me Against the World or The Carter IV, which leaned into their artists’ vulnerability, Peterson seems torn between self-exoneration and self-pity.

For the culture, the album raises important questions. Should an artist’s music be separated from their personal actions? Can prison serve as an authentic space for creative reinvention, or does it risk being a performative shield against accountability? Hip-hop has long celebrated the underdog, but in 2025, with shifting conversations around justice and gender violence, Lanez’s underdog status remains controversial.

One thing is certain—Peterson ensures that Tory Lanez, love him or hate him, refuses to be silenced. But whether hip-hop should listen? That’s a different debate altogether.